R&D: Anarchonomicon's "After the State"

Reading and Deep-Thinking about the transformation of the West into a bunch of Medieval burghs.

Reading and Deep-Thinking Dept.

Welcome to the R&D department, where we stop and THINK about an essay in detail. I choose the essay at random, otherwise I'd only be thinking deeply about essays I love, and I love what I understand, so I'd only understand more what I already understand. Instead - random. I roll a D10 after each essay I read, and if it comes up 0, it gets a deep read.

My goal here is to resist the modern inclination to glide over the surface of thought. Here on Substack I see more people resisting that than any other gathering, and for that, I'm proud. But even so, I see these incredible essays dropped, read somewhat closely, commented on briefly, then almost forgotten. Then we demand another. We can't really expect to build a body of knowledge, really, an alternative to the University system, without deeply considering the work of others.

R&D sessions will be from current material, but also from the archives of Stack's of which I'm a paid subscriber.

Most deep reads take me about eight hours, depending on length. I love every minute. Eight hours doom-scrolling through Twitter would produce...nothing; or perhaps, only stress. Eight hours on an essay? I come away wiser, more knowledgeable, and happier. Even if the essay is garbage. As Confucius say, “It no matter who you walk with, you learn from smart and dumb rocks.”

My essay presupposes you’ve read the original essay. I quote at times for locational reference, but also simply mention sections of the essay without a quote. So without further ado…

Reading and Deep-Thinking About: Anarchonomicon's "After the State"

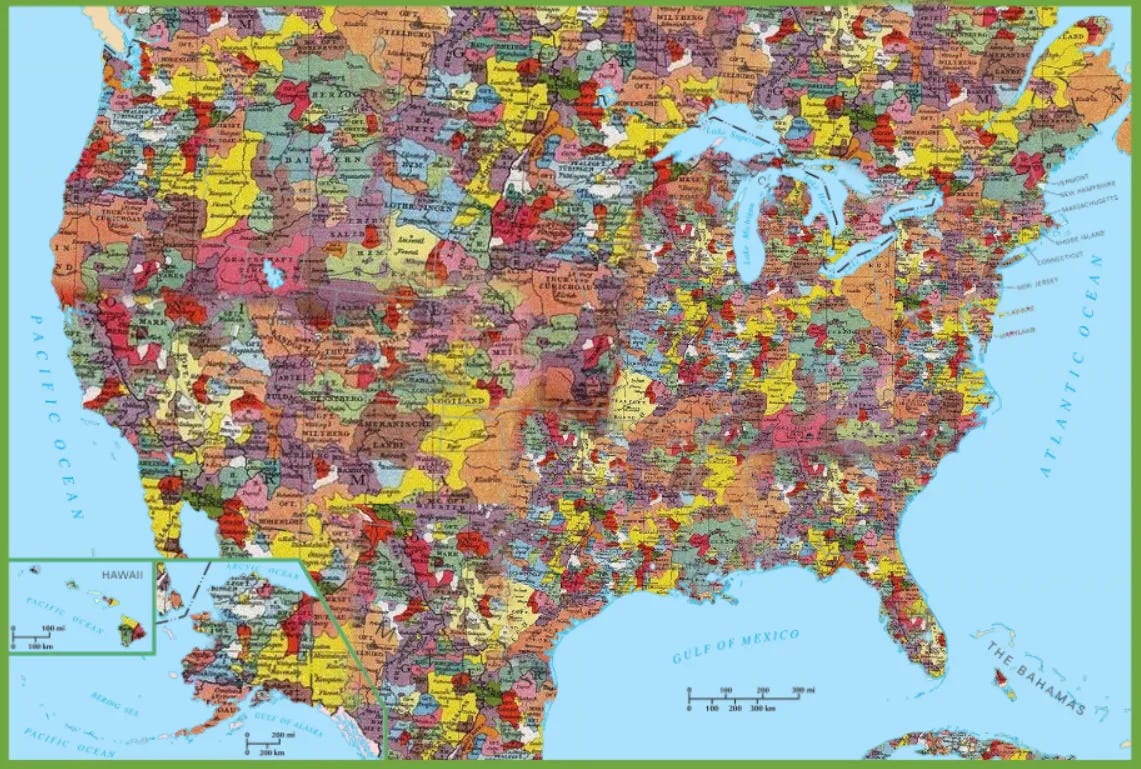

“A post breakup America would probably look closer to this…”

We're introduced to the premise here: America will become a hyper-fractured collection of...what? Not a few regional powers but a shattered collection, and collection might even be too strong a word, of city-states, counties, communes, and what not.

Interesting... The prevalent dread of people who love freedom is that the world is on a relentless progression towards the concentration of power. This has close ties to Christian eschatology (Meaning: "Last Speaking/Study"). Christian's generally believe it's only going to get worse until the End, which will be a global nightmare-state run by the Beast. Also, Christian or not, we see the general progression of things has been towards integration and consolidation; we can't help but think it will go on forever. Kulak's premise is in direct opposition to this, and really, in direct opposition to what might be a civilization-wide intellectual assumption. He has my attention!

"What you may have noticed is there’s really just two great centralizing eras in the history of western civilization… the 300-350 years from the start of Alexander’s conquests til the final centralization of the Roman empire under the Caesars… And the 250-300 year history of modern empire: From approximately 1700-1945."

Yes. Each of the three hundred year periods represent the final consolidation of that era. But "Centralizing Eras" is a big idea that needs explained. He proceeds to do so.

He identifies Centralizing Eras by the prevalence of great heroes. There are heroes pushing consolidation/centralization, and tragic heroes trying to stop it. So we can see Centralizing Eras by the heroes that inhabit them.

Why do Centralizing Eras exist? He's not sure. He argues that technology tends to be universalized, thus identifying which technology, or really any technology at all, as the decisive centralizing factor is difficult. He gives the example of Roman roads, which at first were a decisive technological advantage, but savages can walk on roads as well as scholars, and all roads lead to Rome...

He briefly argues that we know some techs definitely AREN'T centralizing. Capital-intensive tech like knights and aircraft carriers aren't centralizing tech because they aren't universally available.

What is universally available? Complicated manpower. Organization, my friends. Example - The phalanx.

There are many other examples of this decisive organizational technique. One I love is the Rus Vikings, who in typical Viking fashion sailed thousands of miles down various rivers to the heart of the Slavic world and said, "This is ours." A few hundred guys in a few boats conquered millions of Slavs. How? Moxy. And shield wall.

The will to use power is first, then the ability, then finally the technical expression of that power. Without the will to conquer all the Slavs the technical expression of that will, the means, would have never been found.

But even technology that allows for more complicated manpower organization isn't necessarily centralizing, because it can be stolen. In fact, information travel can be decentralizing. As Kulak says, “This is why in the information age technological advantages are disappearing faster and faster.”

The example given is that the phalanx was able to conquer the entire Persian Empire because information traveled so slowly - The Persians couldn't get the information they needed to adapt in time.

I don't agree with this, at least in the Persian example. The Greek phalanx dominated the Classical world for hundreds of years, until it was finally eclipsed by an even more sophisticated human organization, the Roman Maniple.

The Greeks kicked ass for hundreds of years not because other nations or peoples didn't know about the phalanx. They knew about it, but absolutely could NOT do it themselves. You think - What? How hard is it to give a bunch of guys spears and shields and point them all in the same direction? Turns out, very very hard.

Why? Well, that's an essay all its own. But the Greek monopoly on phalanx-tech wasn't lack of awareness. It was lack of...something else.

Example aside - What if information traveled quickly? Proliferation of tech would make comparative advantage hard to obtain, right?

"This is why the information age has been so corrosive to centralization."

He makes here a massive statement. Truly BIG. One reason I love Kulak's stuff is that he just throws ideas and statements like this out there. Waddya think of this? Then he moves on. Love it. Also, hate it. That statement deserves an entire essay.

It's also, possibly, entirely wrong. Or is it? There's an incredible centralizing aspect to technology. The purpose of any technic is to increase efficiency. Using a letter to talk to Grandma is more efficient than walking over there, a telegram more efficient still, and an email most efficient. Then you have technics for talking to EVERYONE, including Grandma, like Facebook.

Each of those techs brings strong centralizing tendencies because efficiency increases at scale. This was true in the industrial age, and is also true in the information age. We can see this in the early web wars, or the early ISP wars, etc. where a huge number of companies were whittled down until only one or two remained. A giant ISP like ATT can offer more speed for a better price than a menagerie of companies. Web hosting isn't done by individuals any more, it's done by a few huge hosting providers. And so on.

So I disagree with his earlier statement:

The very act of making technology more efficient, less cumbersome, and more useful for day to day economic activity destroys most of its military and governing potential. Once its common then everyone has it, and once everyone has it then it isn’t a unilateral or even a multilateral advantage.

Everyone has a smartphone, yes, but there's only two major phone OS providers, and less than a dozen phone manufacturers. One single nation, Taiwan, produces nearly all the chips that make these phones possible. So the possession of the usable aspect of the technic is universal, but the means of production, and the means of control, of the technic decidedly is NOT. The State doesn't need to control all the phones, it just needs to control Apple. And it does.

So at first I'd be inclined to disagree with Mr. Kulak, but there is a factor that he considers later that might prove me wrong. Or at least, makes us both right. We'll get to that later.

Next we get to decentralizing eras. How do we identify them?

"Decentralizing eras are defined by sophisticated capital and skill intensive weapons that can be utilized by relatively few people, and which are widely distributed."

He argues decentralizing eras exist because of a cheap, universally available tech that can rapidly overwhelm manpower-expensive organizational tech. He uses the example of the Bronze Age collapse due to the invasion of the Sea Peoples. For those that know their Bible, the Philistines were Sea Peoples.

But he distinguishes here the tech as capital and skill expensive, but human-quantity cheap. So it's universally an option to be used, but only by a select few.

He also uses the example of knights and castles. Once again I'm not sure I agree with the examples. The Knight was at the pinnacle of a big human organization; behind that one knight wasn't just a squire, but an entire manor. It takes a lot of peasants raising horses, growing grain, mining ore, smithing equipment, tanning leather, and so on to put that knight on a horse.

Same with castles. It takes a lot of peasants to build a castle. Why is Alexander's causeway a human-capital intensive example of centralization, but a giant medieval castle, also human-capital intensive, an example of decentralization? That doesn't make sense.

Swiss pikeman squares ended the dominance of knights. A Swiss pikeman isn't wearing armor or weapons much different than a Greek hoplite from a millennia earlier. None of that changed. What was lost was the ability to arrange squares. So it may be that it's less a decentralizing technic that destroys centralization, as the loss of human-organizational technic needed to accelerate centralization. Knights existed in a vacuum, a civilization pause, that merely needed filled. Roman Legionaries would have crushed Medieval Knights, as would a Greek Phalanx. It wasn't that knights had capital-intensive weapons and armor and thus were able to decentralize society, it's that the human-organizational-intensive technics to easily counter knights had been forgotten.

I must tell the reader that I got quite hung up on this part of the essay. Of course, the first time through I just read it and let it flow over me. But for this reading I came to full, multi-hour stop on the concept of decentralizing eras.

I finally decided I agreed with his concept of decentralization, but disagreed that it's an era that persists. Rather, it's a moment in time.

The Middle Ages weren't a decentralizing era, they were the nascent years of the new modern era. The institutions, mores, and systems we see today were all slowly being built. The collapse of the Roman Empire was a decisive break, and what came after was a new iteration of the West. That takes time. Centuries.

The same for the Bronze Age collapse, which saw the end of Ancient Western civilization and the beginning of the Classical West. It wasn't decentralizing, it was decentralized, then slowly, inexorably, re-centralizing after the collapse.

It's not an era, it's a moment, and it comes quickly. The Bronze Age collapse and the collapse of the Roman Empire both happened in about fifty years, a blink of an eye compared to the centuries of centralization and consolidation that came before.

Let us move on. I agree with him that centralizing eras exist, but I think I part ways with him concerning decentralizing eras, at least, that it's an era; rather, my opinion would be that it's less an era and more a moment, and that what he calls decentralizing eras were more the early stages of centralization - Like a bicycle picking up speed, or a train, the first moments after a full stop it is moving quite slow, but acceleration increases with momentum. The Dark Ages were the West just starting to move again.

Next big question: Where are we in this picture?

"Do we live in a centralizing era?"

He answers no. He argues that, since our modern leaders are pathetic and immemorable, then we must be in a decentralizing era because leaders that get remembered are those from centralizing eras.

"None of our leaders are analogous to the great conquerors."

This is a tenuous argument. But it's only the first argument.

He continues with a brief overview of the Holy Roman Empire. It's a great overview that makes plain how much of a mess the Empire was. Almost every map is an anachronism - It puts something there that wasn't there, namely, coherence. We draw a neat line around an area and declare that, at such and such date, the this or that nation had these boundaries. But it didn't. Kulak does a great job of walking us through how absurd any map of the Holy Roman Empire, or earlier, Greece is, because at no time was allegiance as simple as we like to make it.

Then he continues with an excellent explanation of the complex web of power-holders in most Medieval towns. I can't quote at length so here so just go check it out, it’s about halfway through the essay. It is quite good and went straight to my list of sources for quotation and reference. In short, power was widely diffused in most Medieval cultures.

He then contemplates if perhaps the USA is our modern Holy Roman Empire.

"Now tell me, is there another 3 word national title that’s hotly debated?

To what extent is the USA really United? States? or America?"

With this question he provide's a theory on why centralizing eras end, simply, because "Smaller entities just learn how to fight back."

Historical examples are provided. His theory is that smaller forces eventually learn the organizational techniques of the big powers, and use those techniques to defeat them. The Goths defeated Rome, the Afganis defeated the British/USA, and so on. This doesn't necessarily contradict his earlier theory about decentralization, that it occurs because capital-intensive but high skill technics like boats, knights, and castles shatter central forces, but that theory isn't mentioned here at all.

I agree with the argument; however, I find another question even more pertinent, especially considering we're trying to determine if our own centralizing era is about to end, and that question is: Why then? Why was it in 400 AD that the various Germanic tribes finally shattered the Roman Empire? Yes, they learned Roman army techniques, but the Germans had been in contact with Rome for centuries. Why did it take so long to learn, and what enabled them to finally learn? The massive German swarms that poured across the border were no larger than armies that had been defeated time and again by previous Roman forces. What made those final invasions so effective?

Kulak answers one part of that question, namely, that legacy empires/nations brought colonial subjects in and educated them. This certainly applies to the Roman scenario - We see basically no German names in the lists of consuls, leaders, and generals until around the 350s AD, when they rapidly proliferate. Apparently, getting one's ass kicked by a centralizing power isn't enough to learn how to fight, one has to be brought into bosom of the enemy and slowly learn their ways.

But the second part of the question still bothers me. Why was it that moment that they finally shattered?

My mind goes the same direction as Kulak's. He seems to digress here into an explanation of the State, but I think we're actually getting to the crux of the matter and the answer to why centralizing power eventually becomes brittle and shatters.

His theory here, and it is a good one, and one that has been considered by philosophers for some time, is that the State is a separate entity from the society or government. I agree. The first thing in any civilization is the society - The links between people. The society answers the questions, "Who are we?" and "Why are we here?" and "How should we treat eachother?" As a society becomes more complex it naturally creates a government to help arbitrate the more complex answers to those questions. "Who are we? Well, we're these people, but not those, we keep those people out, and we use the organizational power of the government to do it." And so on.

A place like the Holy Roman Empire was a society filled with governments. *The* government, like we're used to in our modern total-States, didn't exist. The guild was a government. The Church was a government. The noble was a government. And each governed his little part of the society. But eventually one of those governments begins to muscle out all the others, and as Kulak says, "The tale of early modern governance is that of interests of the central government crushing regional interests."

I'd like to point out here that "central" is an anachronism of sorts - The central government became central because it became dominant. Then we look back and label retroactively that particular government "central."

As any one government grows in power an inevitable action happens, one so predictable and constant that we can almost call it a law of nature: Those that love power for power's sake are attracted to that government. If power is the blood of the government, then these would be parasites of the blood. A tick doesn't latch onto a dog because it likes dogs, it likes blood, and the dog happens to have some. In a word, we get bureaucrats who love power. A pox on them.

I slightly part ways with Kulak here - I believe the State *is* the parasite, while he contends that the State is filled *with* parasites. Which is correct? That's a big question that should be answered elsewhere. For more study I heartily recommend Nock's "Our Enemy, the State".

In any case, he comes to the crux of the matter: "Now the bureaucracies that enabled then parasitized then consumed the centralized state, killing off first the absolutists monarchs then the republics that succeeded them, those bureaucracies are killing off the core organs of the state itself."

I believe this answers what, to me, is the most important question of this essay. Why? And... why now? Why do centralizing eras end? And...why is our present time so ripe for a similar collapse?

Kulak mostly focuses on the parasites within the American system, but I believe the problem goes beyond just corrupt bureaucrats controlling nation-states. The West and it's institutions have become almost universally corrupt. This hasn't always been the case. The West, unique to other civilizations, has non-State connective institutions that exercise different types of power. Kulak detailed that so well above. The University system, banking systems, the Catholic Church, and more recently, international organizations like the League of Nations or the UN are all governing institutions. After the fall of Rome this new web of power has slowly grown into its full realization. During those growth years there were sometimes parts of the West that were corrupt, but it wasn't always EVERY part.

As an example, the Catholic Church was wholly corrupt, or rather, reached a state of total corruption in the 13-1400’s AD, but nation-states weren't totally corrupt, nor were the city-states, nor were the various guilds or protobanks. The nascent University system was a big part of correcting the corruption of the Catholic Church.

There was a correcting mechanism of sorts - Any one government could be infested with parasites, but it would be defeated by the others due to parasitic weakness.

Covid was eye-opening in that we saw almost every major institution that made up the West act in a uniformly destructive and idiotic way. They were all corrupt, incompetent, and cowardly. The corrective mechanism was, and is, broken. There's insufficient good to correct the bad, it's all bad. How has this happened? I don't know. But it has.

The metaphor that came to mind thinking of these parasites is the Intellect Devourer from DnD. They consume sentient brains, then once the brain is gone, enter the brain cavity and control the victim's body. Totally gross. That morbidity is one reason I don't play DnD (The movie's great though).

A bureaucrat is someone who benefits from the institution they control and wants the entirety of that benefit for themselves. A parasite. A virus. Like the victim of a Devourer, the institution ceases to perform its function and becomes a shambling flesh-wagon for the Devourer perched up in its head.

This can be quite disturbing for those that loved that person. The person is dead, their brains scooped out and slurped up, but we can, in a way, work with the Devourer and pretend that perhaps they aren't. The Devourer knows this and occassionally lurches about and does something the person used to do. But the person is dead.

In the same way, the University is still there, it sometimes acts like the University, but in our hearts we know that it is dead. The University's body exists entirely for the parasite now. Not for the society.

What if the bureaucrats have entirely taken over? Everything, top to bottom, is run by parasites. The whole room is filled with devoured victims. There's no hero left to purge the corrupt and right the wrongs.

The question of course is, why? Why have all the instutions been taken over? Is it the inevitable fate of every institution? How is it that the whole party is now Devourers? When the first hero went down, assumed a glassy gaze, and ceased to be human, why did the other heroes look away? For a team wipe such as that you'd need one of two scenarios - First, everyone else had become so cowardly and/or stupid the Devourers were able to slowly gain control one person at a time, or two, they gained control so rapidly a response couldn't be organized in time.

An important question to consider. But that's for another time.

I disagreed above with Kulak that information technology was inherently decentralizing, and said that perhaps we could both be right. How?

Here's how - One, technology creates large systems because efficiency increases at scale. Two, parasites are attracted to large systems because they provide a greater basis of power on which to feed. Three, parasitic control of a system leads to total loss of function.

So in a way, information technology can be inherently decentralizing, but perhaps not for the reasons Kulak posits. It might rather be due to colossal institutions being built up and eventually toppled by parasitic control. The eventual collapse of the systems is even more devastating due to their size and near monopoly on function, so the time period after rapid decentralization lasts longer.

It's a question that needs a thorough answer. But that's also for another time.

Continuing on, if in fact every single governing institution of the West has been taken over, it'd make everything oh so brittle. The institutions have ceased to be good at what they do. The bureaucrats don't care, but the institution being good at what it does is crucial to the civilization. There's no Western civilization without the University, without the Church, and so on. We have a complicated civilization, one that takes intelligent governance. If that intelligence is gone, the civilization will be unable to maintain itself at any level of complexity.

Does this mean we've reached the end of the West? That when some external decentralizing force comes, we'll collapse? That like the fall of Rome or the Bronze Age collapse we're on the verge of entering a whole new era?

Kulak's answer: Yes.

Why is America on the verge of collapse? In short, because the Feds don't control the States, the elite are in a dysfunctional state, who actually has power no one can clearly state, and all institutional power has been usurped by The State.

He sees a patchwork of power similar to the Holy Roman Empire. I disagree however that America is similar to HRE Germany. It isn't. HRE Germany didn't have a total-State parasite that had consumed all the vitals of every source of power. It was still a diversified governance. Kulak notes both of these things but I think erroneously equates the two.

America will collapse because it ISN'T like HRE Germany, and in collapsing, will eventually become more stable like HRE Germany. That's possibly an insane statement, I know.

After collapse, Kulak sees an America dominated by various criminal gangs, both legal and illegal. He sees people scrambling to make whole the gap left by a collapsing debt-based currency. He sees crumbling infrastructure. He sees pickup trucks.

No really, pickup trucks could be contributing factor to collapse, and he's probably right:

And of course the Technical, really just the consumer pickup truck, is a logistical marvel and world changing invention for warfare on a par with the warhorse itself. The fact that any ordinary person can transport 1 ton of equipment and themselves 2000 kms in under 24 hrs… RELIABLY....

Just want to point out that no American would transport himself 2000 kilometers in 24hrs. He'd transport himself 1,242 MILES. My truck doesn't do kms. Canadian much, Kulak?

The decentralizing moment, for it will be a moment, not an era, could come soon. We could be living in it right now. It won't be due to inter-parasitic struggle, it will be due to barbarians, whether from within or from without. If we do something, we can be the barbarians from within. If we do nothing, we're doomed to be conquered by barbarians from without. It could be five years, it could be fifty, but I agree with Kulak that the West is ready to fall.

What the fall will look like depends in a large degree on us. After the fall, well, who knows what that will be? It will be a new Dark Age of sorts, as the scattered pieces slowly start to come back together. But the Dark Ages weren't that dark. And as Kulak shows, medieval society was remarkably free and diverse, with no single power dominating all the others. After the Bronze Age collapse we got the golden age of Classical Greece, which produced thinkers that changed the course of the human race. It's no bad thing for a moldering edifice to finally collapse. If you can survive the building falling over, that is. Best way to survive it - Be a part of the controlled demolition!

In conclusion, I liked this essay. Kulak is an excellent Wrinkle-Finder (See Isaac Simpson's analysis of different successful online personalities). As best I can tell, Kulak’s a voracious reader and it shows. He affects a carefree style of writing that's disinterested in niceties like proper spelling, punctuation, or organization. For shorter pieces this is a lot of fun and makes for fast, easy reading. For larger essays, however, all those niceties move beyond nice and into, perhaps, necessarry. I found it difficult to follow at times.

The benefit though, is that Kulak is able to produce an impressive volume of work. I'm happily a paid subscriber for those many "Ah-Ha!" moments and food for thought that Kulak provides. Thank you, sir, and bravo.